6.4 Waimakariri [WAI]

"The Waimakariri rises in the snows of the Southern Alps and its waters never fail. Like other snow fed rivers its flow tends to be greater in warm weather when the snows are melting [creating freshes]… Thus the natural tendency of the river is a periodic flushing out of its channels, which wind among braided shingle beds a kilometre wide when the level is low." (2)

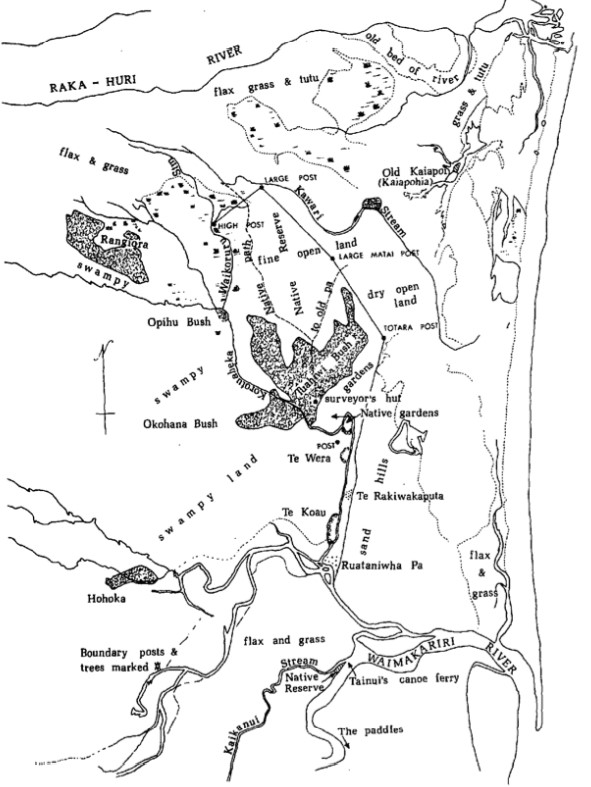

This section addresses issues of particular significance to the lands and waters of the Waimakariri catchment, a large catchment stretching from Ngā Tiritiri o Te Moana to Te Tai o Mahaanui to the high country, and encompassing a number of landscape features: mountains, high country lakes and wetlands, foothills, forests and grasslands, plains, spring fed lowland streams and coastal lagoons (Map 10).

The name Waimakariri refers to the cold (makariri)

mountain fed waters of this braided river. The river was part of a larger network of ara tawhito linking the east coast of Te Waipounamu to the mahinga kai resources of the high country and the pounamu resources of Te Tai Poutini. The Waimakariri and its tributary the Ruataniwha (Cam River) were two of three waterways (the other being the Rakahuri) that continued to sustain Ngāi Tahu even after the land purchases in Canterbury. (1) The region between the Waimakariri and Rakahuri River was of particular importance for mahinga kai.

The cultural, spiritual, historical and traditional significance of the Waimakariri landscape to Ngāi Tahu history and identity is acknowledged in the NTCSA 1998. Moana Rua (Lake Pearson) is a Statutory Acknowledgement site. Kura Tawhiti is a Statutory Acknowledgement site and a Tōpuni

(see Appendix 7 for schedules). The traditional place

names Maungatere (Mount Grey) and Kapara Te Hau (Lake Grassmere) are recognised under the Act’s dual place names provisions.

As with other braided river catchments in the region, the lower Waimakariri catchment is highly modified by human activity, while much of the upper catchment remains mountainous and wild; a source of life and nourishment for the plains and coast.