5.6 Tangaroa

Wāhi Tuarima | Part 5

Ngā Take ā-rohe Me Ngā Kaupapa | Regional Issues and Policy

The sea was before

the land and the sky,

Cleansing, joining.

And where the sea

meets the lands

there are obligations

there that are

as binding as

those of whakapapa.

– Teone Taare Tikao

5.6 Tangaroa [TAN]

This section includes issues and policies related to the realm of Tangaroa, the atua of the sea. In the Ngāi Tahu tradition, Tangaroa was the first husband of Papatūānuku.

As emphasized in the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (2010), tāngata whenua have a traditional and continuing cultural relationship with areas of the coastal environment, including places where we have fished and lived for generations. The association of Ngāi Tahu to the Canterbury coast is acknowledged in the NTCSA 1998, whereby Te Tai o Mahaanui (the Selwyn Banks Peninsula Coastal Marine Area) and Te Tai o Marokura (the Kaikōura Coastal Marine Area) are recognised as coastal statutory acknowledgements (see Appendix 1 for a map). Te Tai o Mahaanui is also source of the name for this IMP, acknowledging the coastal waters and tides that unite the six Papatipu Rūnanga.

The RMA 1991 provides protection for the coastal environment and the relationship of Ngāi Tahu to it as a matter of national importance:

- Section 6 (a): The preservation and protection of the natural character of the coastal environment (including the coastal marine area), wetlands, and lakes and rivers and their margins;

- Section 6 (b): Protection of outstanding natural features and landscapes;

- Section 6 (e): the relationship of Māori and their culture and traditions with their ancestral lands, water, sites, wāhi tapu, and other taonga; and

- Section 6 (f): Protection of historic heritage.

Ngā Paetae | Objectives

(1) There is a diversity and abundance of mahinga kai in coastal areas, the resources are fit for cultural use, and tāngata whenua have unhindered access to them.

(2) The role of tāngata whenua as kaitiaki of the coastal environment and sea is recognised and provided for in coastal and marine management.

(3) Discharges to the coastal marine area and the sea are eliminated, and the land practices that contribute to diffuse (non-point source) pollution of the coast and sea are discontinued or altered.

(4) Traditional and contemporary mahinga kai sites and species within the coastal environment, and access to those sites and species, are protected and enhanced.

(5) Mahinga kai have unhindered access between rivers, coastal wetlands, hāpua and the sea.

(6) The wāhi taonga status of coastal wetlands, hāpua and estuaries is recognised and provided for.

(7) The marine environment is protected by way of tikanga-based management of fisheries.

(8) Coastal cultural landscapes and seascapes are protected from inappropriate use and development.

Ngā Take | Issues of Significance

- TAN1: Statutory acknowledgements

- TAN2: Coastal water quality

- TAN3: Coastal wetlands, estuaries & hāpua

- TAN4: Protecting customary fisheries

- TAN5: Foreshore and seabed

- TAN6: Marine culture heritage

- TAN7: Coastal land use and development

- TAN8: Access to coastal environment

- TAN9: Offshore oil exploration

- TAN10: Aquaculture

- TAN11: Beached marine mammals

- TAN12: Freedom camping

TAN1: Statutory Acknowledgements

Issue TAN1: Recognition of the coastal Statutory Acknowledgements beyond the expiry of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement (Resource Management Consent Notification) Regulations 1999.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN1.1 To require that local government recognise the mana and intent of the Te Tai o Mahaanui and Te Tai o Marokura Coastal Statutory Acknowledgements beyond the expiry of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement (Resource Management Consent Notification) Regulations 1999. This means:

(a) The existence and location of the SAs will continue to be shown on district and regional plans and policy statements;

(b) Councils will continue to provide Ngāi Tahu with summaries of resource consent applications for activities relating to or impacting on SA areas (reflecting the information needs identified in this IMP);

(c) Councils will continue to have regard to SAs in forming an opinion on affected party status; and

(d) Ngāi Tahu will continue to use SAs in submissions to consent authorities, the Environment Court and the Historic Places Trust, as evidence of the relationship of the iwi with a particular area.

TAN1.2 To work with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu to:

(a) Extend the expiry date of the Statutory Acknowledgement provisions; and

(b) Advocate for increasing weighting and statutory recognition of IMP in the RMA 1991, so as to reduce the need for provisions such as Statutory Acknowledgements.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Statutory Acknowledgements were created in the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement as a part of suite of instruments designed to recognise the mana of Ngāi Tahu in relation to a range of sites and areas, and to improve the effectiveness of Ngāi Tahu participation in RMA 1991 processes. Statutory Acknowledgments are given effect by recorded statements of the cultural, spiritual, historical, and traditional association of Ngāi Tahu with a particular area (see Schedule 100 of the NTCSA 1998 for a statement of Ngāi Tahu associations with Te Tai o Marokura, and Schedule 101 for Te Tai o Mahaanui, included in Appendix 7).

Statutory Acknowledgments have their own set of regulations that implement Deed of Settlement provisions such as resource consent notification. The Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement (Resource Management Consent Notification) Regulations 1999 have a 20 year life span and therefore expire in 2019. Statutory Acknowledgements continue to be relevant and necessary to the effective participation of tāngata whenua in RMA 1991 processes. The purpose of Policy TAN.1 is to ensure that plans, policy statements and resource consents relevant to the Te Tai o Marokura and Te Tai o Mahaanui Coastal Statutory Acknowledgements continue to recognise the significance of these coastal areas to Ngāi Tahu.

TAN2: Coastal Water Quality

Issue TAN2: Coastal water quality in some areas of the takiwā is degraded or at risk as a result of:

(a) Direct discharges contaminants, including wastewater and stormwater;

(b) Diffuse pollution from rural and urban land use;

(c) Drainage and degradation of coastal wetlands; and

(d) The cumulative effects of activities.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

Standards

TAN2.1 To require that coastal water quality is consistent with protecting and enhancing customary fisheries, and with enabling tāngata whenua to exercise customary rights to safely harvest kaimoana.

Discharges to coastal waters

TAN2.2 To require the elimination of all direct wastewater, industrial, stormwater and agricultural discharges into the coastal waters as a matter of priority in the takiwā.

TAN2.3 To oppose the granting of any new consents enabling the direct discharge of contaminants to coastal water, or where contaminants may enter coastal waters.

TAN2.4 To ensure that economic costs are not allowed to not take precedence over the cultural, environmental and intergenerational costs of discharging contaminants to the sea.

TAN2.5 To continue to work with the regional council to identify ways whereby the quality of water in the coastal environment can be improved by changing land management practices, with particular attention to:

(a) Nutrient, sediment and contaminant run off from farmland and forestry;

(b) Animal effluent from stock access to coastal waterways; and

(c) Seepage from septic tanks in coastal regions.

TAN2.6 To require that the regional council take responsibility for the impacts of catchment land use on the lakes Wairewa and Te Waihora, and therefore the impact on coastal water quality as a result of the opening of these lakes and the resultant discharge of contaminated water to the sea.

TAN2.7 To require stringent controls restricting the ability of boats to discharge sewage, bilge water and rubbish in our coastal waters and harbours.

Ki Uta Ki Tai

TAN2.8 To require that coastal water quality is addressed according to the principle of Ki Uta Ki Tai. This means:

(a) A catchment based approach to coastal water quality issues, recognising and providing for impacts of catchment land and water use on coastal water quality.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Coastal water quality is an important issue with regard to protecting the mauri of the coastal environment and the ability of tāngata whenua to harvest kaimoana.

The use of Te Tai o Mahaanui to treat and dispose of wastewater is inconsistent with tāngata whenua values and interests. Ngāi Tahu policy is unchanged through the generations: water cannot be used as a receiving environment for waste (see Section 5.3 Issue WM6). Currently, urban and community wastewater is discharged into Pegasus Bay, Whakaraupō and Akaroa Harbour. All three of these areas are immensely significant for mahinga kai, and eliminating these wastewater discharges is a priority for tāngata whenua. The cultural, environmental and intergenerational cost of discharging waste to the sea is significant. As the hearing commissioners for a consent application to continue to discharge wastewater to Whakaraupō cautioned:

We see great danger in allowing financial planning processes to drive decisions regarding the sustainable management of natural and physical resources. (1)

Coastal water quality is also affected by non-point source or diffuse pollution, including nutrient run off from agricultural land, stock access to coastal waterways and stormwater run off from the urban environments. The coastal environment is the meeting place between Papatūānuku and Tangaroa - with coastal processes and influences often extending a considerable distance inland, and inland activities often having a direct impact on the coastal environment. This is particularly evident in the bays of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū, where the physical geography of the catchments means that the distance between land use and coastal water quality is relatively short and steep (see Section 6.7 Koukourārata for a good discussion of this issue).

Coastal water quality is also an issue where lakes that have poor water quality as a result of catchment land use are opened to the sea (see Section 6.10 Te Roto o Wairewa and Section 6.11 Te Waihora).

Cross reference:

» Issue TAN3: Coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua

» General policy on water quality (Section 5.3 Issue WM6)

» General policy on waste management (Section 5.4 Issue P7)

» Section 6.4 (Waimakariri): Issue WAI1

» Section 6.6 (Whakaraupō): Issue WH1

» Section 6.8 (Akaroa): Issue A1

TAN3: Coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpu

Issue TAN3: Protecting the ecological and cultural values of coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN3.1 To require that coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua are recognised and protected as an integral part of the coastal environment, and for their wāhi taonga value as mahinga kai, or food baskets, of Ngāi Tahu.

TAN3.2 To require that local authorities recognise and address the effects of catchment land use on the cultural health of coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua, particularly with regard to sedimentation, nutrification and loss of water.

TAN3.3 Environmental flow and water allocation regimes must protect the cultural and ecological value of coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua. This means:

(a) Sufficient flow to protect mahinga kai habitat and indigenous biodiversity and maintain sea water freshwater balance;

(b) Water quality to protect mahinga kai habitat and indigenous biodiversity;

(c) Sufficient flow to maintain, or restore, natural openings from river to sea;

Hāpua as indicators

TAN3.4 To promote the monitoring of cultural health and water quality at hāpua to monitor catchment health and assess progress towards water quality objectives and standards.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Historically the coastal areas of Ngā Pākihi Whakatekateka o Waitaha were dominated by wetlands and coastal lagoons. The areas between the Waipara and Kōwai rivers, Rakahuri and Waimakariri rivers, and Te Waihora and the Rakaia River were well known as food baskets of Ngāi Tahu given the richness of mahinga kai resources found in coastal wetlands such as Tūtaepatu, Te Waihora and Muriwai, and hāpua at the mouths of rivers. Te Ihutai, the estuary of the Ōtakaro and Ōpawaho rivers, was a significant settlement and food gathering site for generations of Ngāi Tahu.

The extent and cultural health of coastal wetlands, estuaries and lagoons has declined significantly as a result of both urban and rural land use, and this has had a marked impact on mahinga kai resources and opportunities (see Case Study: Muriwai). The intrinsic and cultural value of these ecosystems requires an immediate and effective response to issues such as wastewater and stormwater discharges, sedimentation and nutrient run off. Objective 1 of the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (2010) is concerned with safeguarding the integrity, form, functioning and resilience of the coastal environment and its ecosystems, and this includes coastal wetlands, estuaries and hāpua

Ngāi Tahu recognise hāpua as excellent indicators of catchment health and the state of the mauri of a river. At the end of the river and the bottom of the catchment, water quality in hāpua reflects our progress in the wider catchment towards meeting water quality objectives and standards, and restoring the mauri of our waterways.

"The water that some feel is going to waste by flowing into the sea is actually feeding our hāpua."

IMP hui participants

"... the health of the hāpua of rivers is a way we can monitor the success of our zone plans, as the results of all land and water use find their way to the hāpua."

IMP Working Group

Is water flowing into the sea surplus water?

For tāngata whenua, water flowing out to sea is not surplus water, or ‘wasted’ water; it is a crucial part of the water cycle. Floods and freshes play an important role in maintaining the shape and character of the river, cleansing, moving sediment, and opening the river mouth to allow native fish migration. When river flows are reduced, the riverine and coastal ecological processes and balance between fresh water and seawater also gets disrupted. Saline water may start intruding inwards, swallowing the beaches and eroding the coast.

CASE STUDY: Muriwai

Muriwai (Cooper’s Lagoon) is a remnant coastal wetland between Taumutu and the Rakaia River. Historically Muriwai joined Te Waihora to the east. It was a place where tāngata whenua caught tuna for manuhiri , and therefore had special value as mahinga kai. Under section 184 of the NTCSA 1998, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu owns the bed of Muriwai fee simple. The decline of tuna populations in Muriwai is a concern for tāngata whenua, along with the effects of adjacent rural land use.

“…Muriwai is a very important place to tāngata whenua. This is place where we caught eels for the visitors (manuhiri). This place has changed now. There is silt in it now, and it is not as deep, and there are no more eels (except for the ones Fish and Game released in there).” Uncle Pat Nutira

“Mum used to go all the way down to Muriwai and spear eels down there. She used to be in water that was up

to her waist, and she used to have flax tied around her waist. And every time she speared the eels she used to string them up and they used to go along like that until they go about a dozen or more. And then they would come ashore. She would thread the flax through the hole underneath and string them up through their mouth. The eels at the Muriwai were different from the lake. They were sort of green belly eels, not like the silver-bellies that you get from the lake.” Taua Jane N. Wards (nee Martin).

“…the better eels were from Muriwai and the whitebait at Coopers Lagoon. When we used to go whitebaiting, we would drive the horse and cart down to the beach to Coopers Lagoon and go whitebaiting there, because the Lake wouldn’t be open at Lake Ellesmere. If the Lake was open, you could stand in our kitchen and look down at the Lake Opening… if the seagulls were dipping you knew to run your net down to the Lake, catch a feed, run home again and they would still be alive.” Aunty Ake Johnson

“…I liked it when fishing for tuna at Muriwai. The tuna there are a very special tuna with a different colour and even size. The skin was a golden colour different to the ordinary black eel. When we used the patu to kill the eels, it was important to strike just below the head as every useful part of the flesh should not be damaged. If it was marked or damaged these could be seen when you pawhara the eel. When served to manuhiri or given as a koha you wanted them to see the lovely golden colour of the flesh.” Ruku Arahanga

Sources: Interviews with kaumātua from Te Taumutu Rūnanga, in:

a) Te Taumutu Rūnanga and Te Waihora Eel Management Committee: Nature and Extent of the Customary Eel Fishery (D. O’Connell), and

b) the Te Taumutu Rūnanga Natural Resource Management Plan 2002.

Cross reference:

» General policy on wetlands, waipuna and riparian margins (Section 5.3 Issue WM13)

TAN4: Tools to protect Customary Fisheries and the Marine Environment

Issue TAN4: Tikanga-based management tools for protecting and enhancing the marine environment and customary fisheries.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN4.1 The most appropriate tools to protect and enhance the coastal and marine environment are tikang abased customary fisheries management tools, supported by mātauranga Māori and western science, including:

(a) Taiāpure;

(b) Mātaitai;

(c) Rāhui; and

(d) Tāngata tiaki/kaitiaki.

TAN 4.2 To oppose the establishment of marine reserves in areas of significance to customary fishing, wāhi tapu, or where it could inhibit the development of mātaitai or taiāpure.

TAN 4.3 To support the continued development and use of the Marine Cultural Health Index as a tāngata whenua values-based monitoring scheme for estuaries and coastal environment that is part of the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu’s State of the Takiwā Programme.

TAN 4.4 To continue to investigate and implement kaimoana reseeding projects in the takiwā where traditional stocks are degraded.

TAN 4.5 To continue to develop and establish sound research partnerships with the regional council, Crown Research Institutes, government departments, universities and other organisations to address issues of importance to tāngata whenua regarding the management of the coastal and marine environment.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

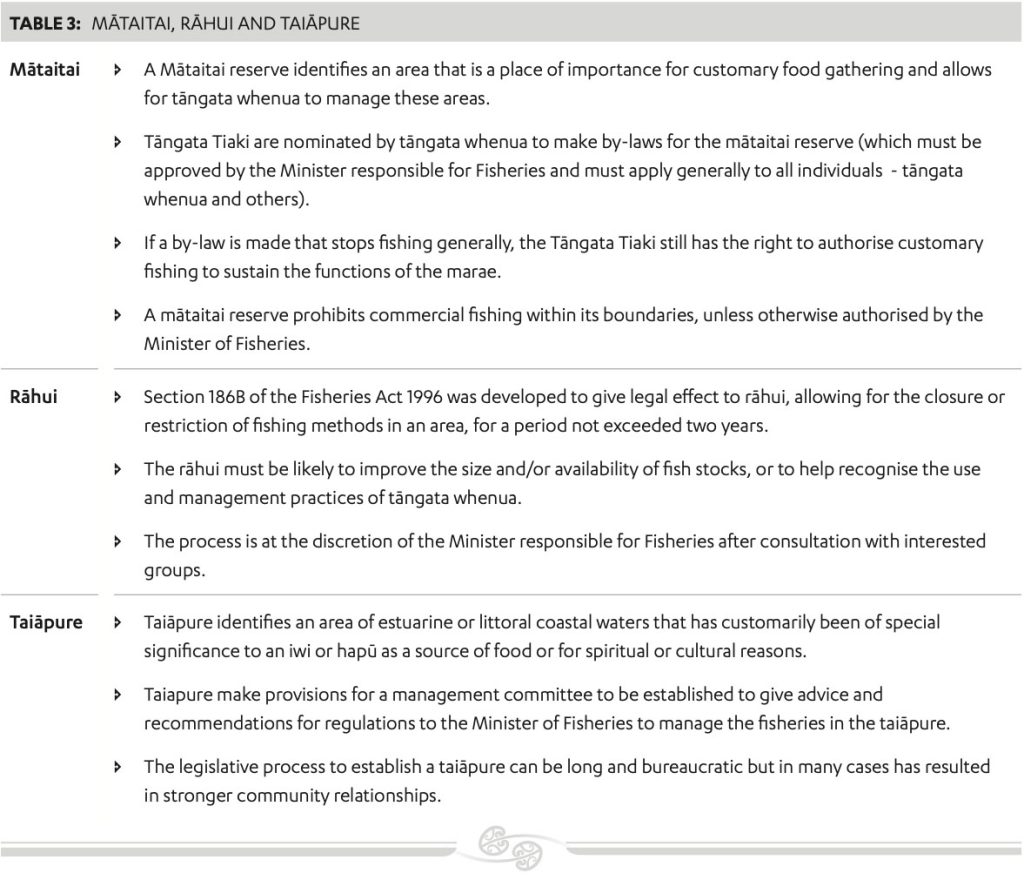

Taiāpure, mātaitai and rāhui are area management tools provided for under the Fisheries Act 1996 (see Table 3). They are designed to protect places of importance for customary food gathering, such as a certain type of fishery or a kōhanga, and ensure that tāngata whenua are involved in local decision-making. They provide for the protection of the marine environment through tikanga-based management of fisheries.

The South Island Customary Fishing Regulations 1999 give effect to non-commercial customary fishing rights and provide the framework for customary fishing area management tools. Under the Regulations, tāngata tiaki/ kaitiaki are nominated by Papatipu Rūnanga and gazetted by the Minister of Fisheries to authorise customary fishing within their rohe moana.

The use of Taiāpure and Mātaitai to protect the marine environment is complemented by other mechanisms that apply to freshwater and coastal sites, including the fee simple title to the beds of coastal lakes and lagoons under the NTCSA 1998 (e.g. Te Waihora and Muriwai) and general fisheries legislation (e.g that sets Te Roto o Wairewa aside for Ngāi Tahu eel fishing only).

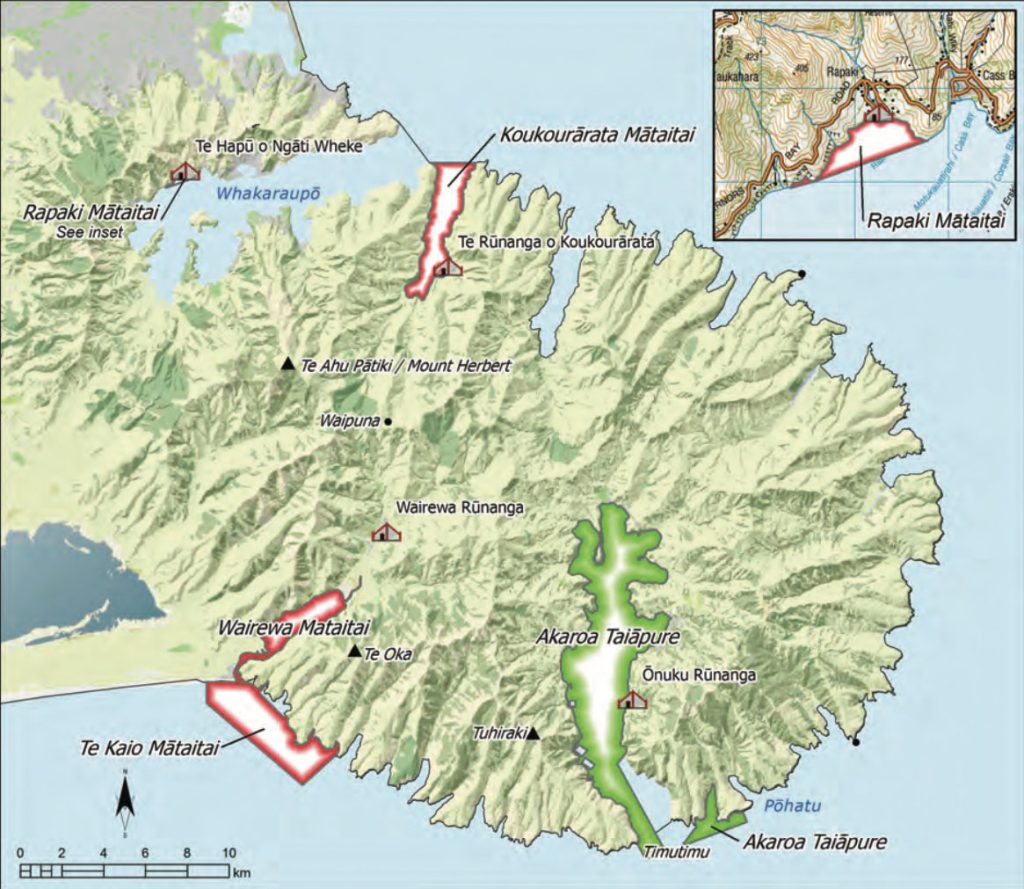

There are four Mātaitai and one Taiāpure in the takiwā covered by this IMP (see Map 3). Part 6 of this plan provides more information on local issues and aspirations associated with each of these.

Map 3: Mātaitai and Taiāpure reserves in the takiwā covered by this IMP

TAN5: Foreshore and Seabed

Issue TAN5: There remains a lack of appropriate statutory recognition for customary rights and interests associated with the foreshore and seabed.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy (2)

TAN5.1 To oppose the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2010 based on:

(a) The unjust and unprincipled tests for establishing customary marine title and customary rights; and

(b) The lack of recognition for tāngata whenua rights and interests in relation to the foreshore and seabed (i.e. “no ownership” regime).

TAN5.2 To continue to contribute to Ngāi Tahu whānui efforts to have customary rights and interests to the foreshore and seabed recognised and provided for in a fair and just way.

TAN5.3 Any replacement model for addressing ownership of the foreshore and seabed must:

(a) Recognise and provide for the expression of mana of whānau/hapū/iwi over the foreshore and seabed; and

(b) Enable Ngāi Tahu Whānui to express their customary rights and interests over particular sites and areas within the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā.

This means that:

(a) Tests and processes for establishing customary title and customary rights must be fair and just, and be able to encompass the rights and interests of all iwi with respect to the areas of the foreshore and seabed of greatest importance to them;

(b) Ownership must be consistent with the Treaty partnership (no Crown ownership, no public ownership);

(c) The Crown should not be able to extinguish customary rights by actions that are inconsistent with the Treaty of Waitangi;

(d) Customary rights should not have to be proven by whānau/hapū/iwi;

(e) Ngāi Tahu must be able access the benefits of any model or regime in a fair and principled way; and

(f) The right to development must be provided for.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

The Ngāi Tahu Takiwā includes a greater area of foreshore and seabed than any other tribal rohe in the country and therefore Papatipu Rūnanga have a particular interest in any frameworks or models that seek to define ownership rights.

Papatipu Rūnanga and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu opposed the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004 and the vesting of ownership of the seabed and foreshore in the Crown. While the replacement Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2010 is different from the Foreshore and Seabed Act in a number of ways, it too falls short in recognising the longstanding rights and interests of Ngāi Tahu in relation to the foreshore and seabed. While the Act eliminates the idea that the Crown owns the foreshore and seabed, it still delegates iwi and hapū interests in a common space, and while it restores access to the High Court for iwi and hapū to claim customary title, the high threshold test to prove continuous and exclusive use of the area since 1840 will be impossible for many iwi and hapū to meet, due to past injustices.

In responding to the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Bill 2010, Ngāi Tahu concluded that while the Bill was different from the Foreshore and Seabed Act in a number of notable ways, the longstanding rights and interests of Ngāi Tahu in relation to the foreshore and seabed are no more capable of recognition under the new Act as they were under the 2004 Act (see Box - Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2010).

Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2010

“The new Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Bill is not the fair and just solution we hoped for and it is a solemn day for us. While the Bill may look different in places, it will not make practical differences for Iwi or the nation. This Bill screws the scrum for Iwi because the tests for rights recognition are near impossible for most Iwi to meet. For the whole nation, this Bill will not improve how our coastal marine area is safe guarded for future generations.”

Source: Mark Solomon, Kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Ngāi Tahu media release. March 24, 2011.

TAN6: Coastal and Marine Cultural Heritage

Issue TAN6: The protection of coastal and marine based cultural heritage values, including cultural landscapes and seascapes.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN6.1 To require that local government and the Crown recognise and provide for the ability of tāngata whenua to identify particular coastal marine areas as significant cultural landscapes or seascapes.

TAN6.2 To require that coastal marine areas identified by tāngata whenua as significant cultural landscapes or seascapes are protected from inappropriate coastal land use, subdivision and development.

TAN6.3 To require that marine cultural heritage is recognised and provided for as a RMA s.6 (e) matter in regional coastal environment planning, to protect the relationship between tāngata whenua and the coastal and marine environment.

TAN6.4 To require that Ngāi Tahu cultural and historic heritage sites are protected from:

(a) Inappropriate coastal land use, subdivision and development;

(b) Inappropriate structures and activities in the coastal marine area;

(c) Inappropriate activities in the marine environment, including discharges; and

(d) Coastal erosion.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Tāngata whenua have a long and enduring relationship with the coastal and marine environment. It is part of the cultural heritage of Ngāi Tahu. Kaimoana is one of the most important values associated with the marine environment and the relationship of Ngāi Tahu to the sea is often expressed through this value. The food supplies of the ocean were regarded as a continuation of mahinga kai on land:

"To Ngāi Tuahuriri fishermen off the coast, the peaks of Maungatere, Ahu Patiki, and other prominent mountains served as marks to locate the customary fishing grounds, for the food supplies of the ocean were regarded as a continuation of the mahinga kai on land." (2)

Other examples of marine cultural heritage values include dolphin habitat and migration routes (particularly Hectors dolphin), whale feeding grounds, migration routes for kōura, sea mounts, reefs, islands and trenches, burial caves, kaimoana, tauranga ika, navigation points and rimurapa.

Cross reference:

» Issue TAN7: Coastal land use and development

» Issue TAN8: Access to coastal environments

» General Policy on cultural landscapes (Section 5.8, Issue CL1)

TAN7: Coastal Land Use and Development

Issue TAN7: Coastal land use and development can have effects on Ngāi Tahu values and the environment.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN7.1 To require that local government and the Crown recognise and provide for the ability of tāngata whenua to identify particular coastal marine areas as significant cultural landscapes or seascapes.

TAN6.2 To require that coastal marine areas identified by tāngata whenua as significant cultural landscapes or seascapes are protected from inappropriate coastal land use, subdivision and development.

TAN6.3 To require that marine cultural heritage is recognised and provided for as a RMA s.6 (e) matter in regional coastal environment planning, to protect the relationship between tāngata whenua and the coastal and marine environment.

TAN6.4 To require that Ngāi Tahu cultural and historic heritage sites are protected from:

(a) Inappropriate coastal land use, subdivision and development;

(b) Inappropriate structures and activities in the coastal marine area;

(c) Inappropriate activities in the marine environment, including discharges; and

(d) Coastal erosion.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Tāngata whenua have a long and enduring relationship with the coastal and marine environment. It is part of the cultural heritage of Ngāi Tahu. Kaimoana is one of the most important values associated with the marine environment and the relationship of Ngāi Tahu to the sea is often expressed through this value. The food supplies of the ocean were regarded as a continuation of mahinga kai on land:

"To Ngāi Tuahuriri fishermen off the coast, the peaks of Maungatere, Ahu Patiki, and other prominent mountains served as marks to locate the customary fishing grounds, for the food supplies of the ocean were regarded as a continuation of the mahinga kai on land." (3)

Other examples of marine cultural heritage values include dolphin habitat and migration routes (particularly Hectors dolphin), whale feeding grounds, migration routes for kōura, sea mounts, reefs, islands and trenches, burial caves, kaimoana, tauranga ika, navigation points and rimurapa.

Cross reference:

» Issue TAN5: Foreshore and Seabed

» Issue TAN 8: Access to coastal environments

» General policies in Section 5.8 – Issue CL1: Cultural landscapes; and Issue CL3: Wāhi tapu me wāhi taonga

» General policy on subdivision and development (Section 5.4 Issue P4)

TAN8: Access to Coastal Environment

Issue TAN8: Ngāi Tahu access to the coastal marine area and customary resources has been reduced and degraded over time.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN8.1 Customary access to the coastal environment is a customary right, not a privilege, and must be recognised and provided for independently from general public access.

TAN8.2 To require that access restrictions designed to protect the coastal environment, including restrictions to vehicle access, do not unnecessarily or unfairly restrict tāngata whenua access to mahinga kai sites and resources, or other sites of cultural significance.

TAN8.3 To require that general public access does not compromise Ngāi Tahu values associated with the coastal environment.

TAN8.4 To oppose coastal land use and development that results in the further loss of customary access to the coastal marine area, including any activity that will result in the private ownership of the foreshore

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Over the last 160 years Ngāi Tahu access to the coastal environment for gathering mahinga kai and carrying out kaitiaki responsibilities has been significantly affected by the degradation and dewatering of sites, loss of mahinga kai resources, and restrictions to physical access. Customary access is a customary right, which means that tāngata whenua must have unencumbered physical access to the coastal marine area.

Tāngata Whenua accept and support the need to restrict public access to sensitive areas to protect habitat and breeding grounds for indigenous species. The impacts of vehicle access on sensitive river mouth and dune environments is an issue of concern in coastal areas. However, while coastal access should be managed to protect indigenous biodiversity and cultural heritage values, it should not unduly restrict customary access. Ngāi Tahu access to sites and resources in the coastal environment must be recognised and provided for independently from general public access. Further, purchasers of land adjacent to the coast cannot be allowed to own (literally or the illusion of) the foreshore, therefore further restricting access.

"Our kaumatua should not have to walk for miles to get their cockles and pipi, and they should not have to go and get a key for access to their traditional mahinga kai places."

Clare Williams, Ngāi Tūāhuriri

"When someone builds a house along the coast they need to know that they do not own the coast or the beach."

Koukourārata IMP hui, 2009

Cross reference:

» General policy on access to wāhi tapu and wāhi taonga (Section 5.8 Issue CL5)

TAN9: Offshore Oil Exploration

Issue TAN9: Is there appropriate environmental policy in place to protect the realm of Tangaroa from effects associated with offshore petroleum exploration and mining?

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN9.1 To require that the Crown and petroleum companies engage in early, and in good faith consultation with Papatipu Rūnanga for any proposed exploration permit blocks or mining permit applications.

TAN9.2 To work with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu to ensure that Ngāi Tahu values and interests are recognised and provided for in the exploration block tendering and mining permit application process.

TAN9.3 To use Section 15(3) of the Crown Minerals Act 1991 (CMA) and the Minerals Programme for Petroleum (2005) provisions to protect areas of historical and cultural significance from inclusion in an offshore exploration permit block or minerals programme.

TAN9.4 To assess exploration and mining permit applications with particular attention to:

(a) Does the company have an engagement strategy in place for engagement with indigenous peoples? and;

(b) Potential effects on:

(i) Marine cultural heritage, including traditional fishing grounds;

(ii) Areas which are significant to whānau, hapū and iwi for various reasons, including places to gather food, settlements, wāhi tapu sites, meeting places and burial grounds;

(iii) Habitat for marine mammals;

(iv) Productivity of area; and

(v) Health of fish stocks.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

There are three types of activities that relate to offshore petroleum activities: prospecting (reviewing and collating existing information), exploration and/or drilling (mining).

Tāngata whenua have concerns that national and regional government do not have appropriate environmental policy in place to protect the realm of Tangaroa from offshore oil mining and exploration. These activities have the potential to affect Ngāi Tahu values and interests, including traditional fishing grounds, marine mammal habitat and cultural heritage sites.

Section 15(3) of the Crown Minerals Act 1991 (CMA) states that on request of an iwi, a minerals programme may provide that defined areas of land of particular importance to its mana are excluded from the operation of the minerals programme or must not be included in any permit. The Minerals Programme for Petroleum (2005) also sets out the Crown’s responsibility for the active protection of areas of particular importance to iwi. Early and on-going engagement with tāngata whenua by both the Crown and petroleum companies is critical to the identification and protection of areas of importance to Ngāi Tahu.

Cross reference:

» General policy on mining and quarrying (Section 5.4 Issue P13)

TAN10: Aquaculture

Issue TAN10: Papatipu Rūnanga have specific rights and interests associated with where and how aquaculture takes place.

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

Allocation and use of coastal space

TAN10.1 To require that Ngāi Tahu have an explicit and influential role in decision-making regarding the allocation and use of coastal space for aquaculture, recognising:

(a) Ngāi Tahu interests in the coastal marine area through a whakapapa relationship with Tangaroa, and through the tikanga of “mana whenua, mana moana”;

(b) Ngāi Tahu customary rights in respect of the foreshore and seabed and associated waterways;

(c) The coastal marine area as the domain of Tangaroa, and a taonga guaranteed to the iwi by virtue of Article 2 of the Treaty of Waitangi;

(d) Ngāi Tahu customary fishing rights and interests guaranteed under, or pursuant to, the Treaty that have historically been recognised by the Waitangi Tribunal and the ordinary courts; and

(e) Ngāi Tahu entitlements to coastal space, as per the NTCSA 1998 and Māori Commercial Aquaculture Settlement Act 2004.

TAN10.2 To require that the regional council recognise and give effect to the particular interest and customary rights of Ngāi Tahu in the coastal marine area by:

(a) Ensuring that Ngāi Tahu is involved in the decision making process for the establishment of Aquaculture Areas; and

(b) Providing opportunities for Ngāi Tahu to identify exclusion areas for aquaculture.

Ngāi Tahu Seafood

TAN10.3 To require that Ngāi Tahu Holdings Group (Ngāi Tahu Seafood) engage with Papatipu Rūnanga when considering marine farming ventures. Customary, non-commercial aquaculture

TAN10.4 To require that current and future regional aquaculture policy recognises and provides for the ability of Papatipu Rūnanga to develop aquaculture for customary, non-commercial purposes (i.e. to support, grow and supplement existing/depleted mahinga kai).

Assessing aquaculture proposals

TAN10.5 To assess proposals for aquaculture or marine farms on a case by case basis with reference to:

(a) Location and size, species to be farmed;

(b) Consistency with Papatipu Rūnanga aspirations for the site/area;

(c) Effects on natural character, seascape and marine cultural heritage values;

(d) Visual impact from land and water;

(e) Effects on customary fishery resources;

(f) Monitoring provisions;

(g) Cumulative and long term effects;

(h) Impact on local biodiversity (introducing species from outside the area); and

(i) Impacts on off-site species.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Aquaculture is the practice of farming in the water: cultivating kaimoana in marine spaces. There are several marine farms in the takiwā, including at Koukourārata, Pigeon Bay, Beacon Rock, Menzies Bay and Akaroa Harbour.

Aquaculture is not new for Ngāi Tahu. Shellfish seeding is a traditional form of aquaculture still practiced today. Rimurapa was traditionally used to transport live shellfish from one location to another, to seed new beds either with new varieties or to assist in the build up of existing depleted stocks.

A second form of aquaculture involved the storage of kaimoana in taiki, or coastal storage pits. Pits were usually hollows in the rocks that would be covered by the tide at high water, and were used to store shellfish such as paua and mussels. Historically, tāngata whenua living at Koukourārata would travel to a neighbouring bay in the autumn, make up small beds of shellfish and store them under piles of rocks for the winter(5).

The purpose of Policies TAN10.1 to TAN10.5 is to ensure that Papatipu Rūnanga have a say in how and where aquaculture occurs. The policies enable Papatipu Rūnanga to promote aquaculture opportunities that are sustainable, and avoid those that will have significant effects. Inappropriate aquaculture locations and unsustainable practices have the potential to compromise values and resources important to Ngāi Tahu. Sustainable aquaculture has the potential for significant contributions to the cultural, social and economic well-being of Ngāi Tahu and the wider community.

Aquaculture and marine farming proposals need be considered on a case by case basis. Papatipu Rūnanga may identify areas that are inappropriate or desirable for aquaculture, based on the specific values located there. For example, particular areas of Akaroa Harbour have special values because of their spiritual status, including areas where submerged caves of high wāhi tapu value are located. Ngāi Tahu traditionally did not use these areas for mahinga kai, and therefore marine farming would also be inappropriate (See Section 6.8).

"Our kaumatua should not have to walk for miles to get their cockles and pipi, and they should not have to go and get a key for access to their traditional mahinga kai places."

Clare Williams, Ngāi Tūāhuriri

"When someone builds a house along the coast they need to know that they do not own the coast or the beach."

Koukourārata IMP hui, 2009

Information resource:

» Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu 2002. Defining Aquaculture Management Areas From a Ngāi Tahu Perspective. Report prepared for Environment Canterbury.

» Crengle, D. 2000, with Te Rūnanga o Onuku, Wairewa Rūnanga and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Akaroa Harbour Marine Farms Cultural Impact Assessment.

TAN11: Beached Marine Mammals

Issue TAN11: Freedom camping is having effects on the environment and Ngā Tahu values

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN11.1 The cultural, spiritual, historic and traditional association of Ngāi Tahu Whānui with marine mammals, and the rights to exercise rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga over marine mammals is guaranteed by Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

TAN11.2 The relationship between Ngāi Tahu and the Department of Conservation for the recovery, disposal, storage and distribution of beached marine mammals shall be guided by the principles of partnership, recognising:

(a) The relationship of Ngāi Tahu to marine mammals, as per Policy TAN11.1; and

(b) The Department of Conservation’s statutory responsibility for marine mammals under the Marine Mammals Protection Act 1978 and the Conservation Act 1987.

TAN11.3 To require that engagement between Papatipu Rūnanga and other agencies regarding beached marine mammals occurs as per the processes set out in the Draft Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Marine Mammal Protocol (2004), and the Interim Guidelines for the Initial Notification and Contact between the Department of Conservation and Ngāi Tahu over Beached Marine Mammals (2004).

TAN11.4 To require that Papatipu Rūnanga are involved in the determination of burial sites for beached whales that do not survive, and that burial locations are retained as taonga and therefore protected from inappropriate use and development.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

The beaching of a whale holds immense cultural significance for the hapū affected by the beaching. Whales feature significantly in Ngāi Tahu creation, migration and settlement traditions. In pre-European times, the natural beaching of whales was considered an act of the gods providing the gift of life for people, as reflected a whakataukī used in evidence to the Ngāi Tahu Fisheries Claim:

He taoka no Takaroa

i waihotia mo tātou

ko te tohora ki uta

This whale cast on the beach

Is the treasure left to us all

By the great god Takaroa.

The Department of Conservation has a legal responsibility to protect, conserve and manage marine mammals. In recognising the importance of marine mammals to each party, Ngāi Tahu and the Department of Conservation developed a draft protocol and interim guidelines to manage beached marine mammals in the Ngāi Tahu Takiwā. The documents set out the process Ngāi Tahu wish to take in responding to beached marine mammals, including recovery, use, storage, distribution and burial of beached marine mammals and marine mammal materials

Information resources:

» Draft Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Marine Mammal Protocol (2004). http://www.Ngāitahu.iwi.nz/Ngāi- Tahu-Whanui/Natural-Environment/Environmental-Policy-Planning/Guidelines-For-Beached-Marine-Mammals.php

» Interim Guidelines for the Initial Notification and Contact between the Department of Conservation and Ngāi Tahu over Beached Marine Mammals (2004). http://www.Ngāitahu.iwi.nz/Ngāi-Tahu-Whanui/ Natural-Environment/Environmental-Policy-Planning/ Guidelines-For-Beached-Marine-Mammals.php

TAN12: Freedom Camping

Issue TAN12: Freedom camping is having effects on the environment and Ngā Tahu values

Ngā Kaupapa / Policy

TAN12.1 To work with local authorities, the Department of Conservation and the wider community to identify areas where freedom camping is prohibited or restricted.

TAN12.2 To support the use of incentives and information as tools to encourage campers to camp in designated, serviced sites as opposed to freedom camping.

He Kupu Whakamāhukihuki / Explanation

Freedom camping refers to camping in a caravan, bus, car, tent or campervan in locations such as rest areas, reserves, beaches, car-parks, roadsides, and lay-bys. Freedom camping often creates issues associated with litter and human waste being left behind by campers. Akaroa and the catchment of Te Roto o Wairewa are two areas where freedom camping is of particular concern.

Under the Freedom Camping Act 2011, freedom camping is considered a permitted activity everywhere in a local authority (or DOC) area, except at those sites where it is specifically prohibited or restricted. This reverses the approach taken by some current bylaws which designate places where freedom camping is allowed, and generally prohibits it everywhere else.

END NOTES / REFERENCES

Decision of Hearing Commissioners for consents to discharge treated wastewater to Whakaraupō (2010, para 209).

The information and polices in this section are based on the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu submission on the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Bill 2010 (November 2010), and the document Ngāi Tahu Whānui Positions On the Crown’s Proposed Foreshore and Seabed Replacement Framework, prepared by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

Evison, H. and Adams, M. 1993. Land of memories: A contemporary view of places of historical significance in the South Island of New Zealand, p.23

Ngāi Tahu Sea Fisheries Report 1991, 3.79.

Te Whakatau Kaupapa p. 4-19.