Ka hāhā te tuna ki te roto

If the lake is full with eels

Ka hāhā te reo ki te kāika

If the home resounds with speaking

Ka hāhā te takata ki te whenua

The land will be inhabited by people

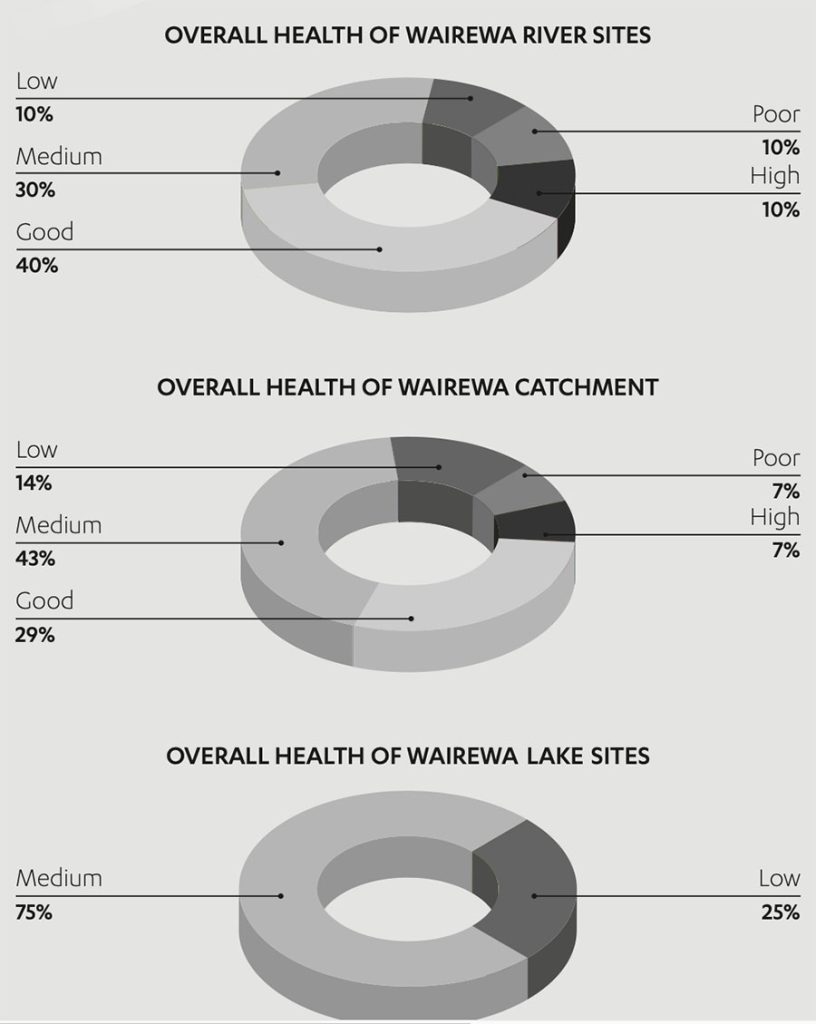

This section addresses issues of particular significance in the catchment of Te Roto o Wairewa. The catchment is centered on the lake, and includes Western and Ōkuti Valleys and the eastern end of Kaitōrete Spit (Map 22).

Over the last 160 years, the catchment has been dramatically modified and mahinga kai values severely degraded. The majority of native forest cover was removed between 1860 and 1890 to open up the land for agricultural and pastoralland use, resulting in massive reductions in native bird and plant species. The level of Te Roto o Wairewa has been controlled for flood protection since the 19th century.

Te Roto o Wairewa is a Statutory Acknowledgement site, recognising the mana of Ngāi Tahu with regard to the lake and guaranteeing tribal involvement in management. Schedule 71 of the NTCSA 1998 is a statement of Ngāi Tahu’s cultural, spiritual, historic, and traditional association to the lake (see Appendix 7). The lake is also one of only two customary lakes in Aotearoa, the other being Horowhenua. This means that only persons belonging to the Ngāi Tahu iwi can take tuna from the lake.